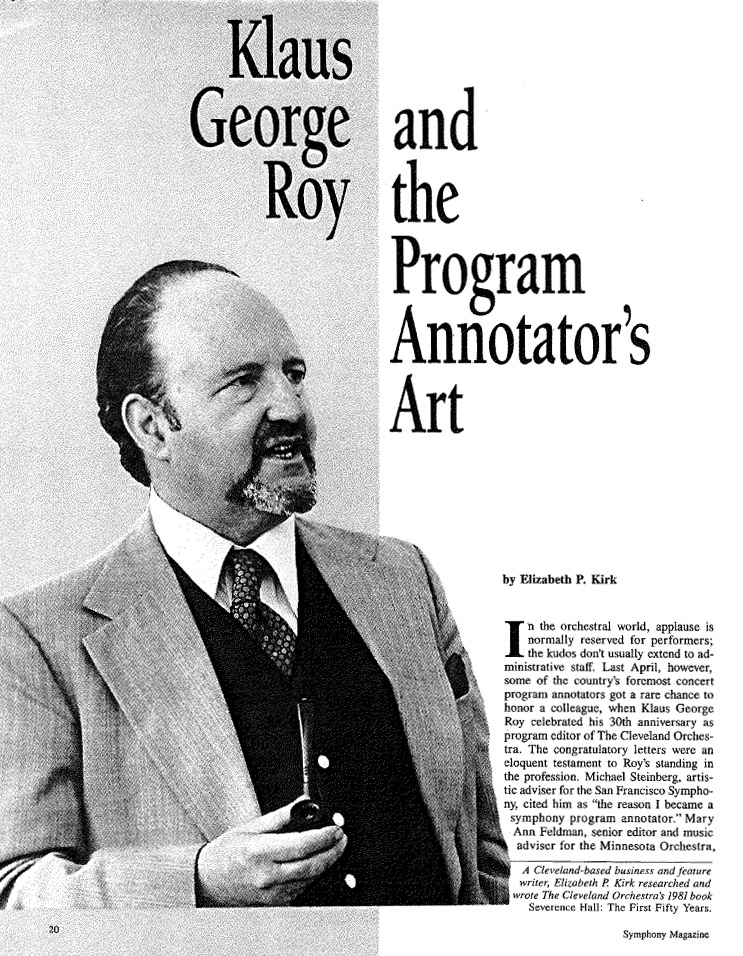

Over six decades, Klaus Roy enjoyed extraordinary success as a writer, composer, music critic, record and program annotator, radio interviewer, concert narrator, teacher and lecturer.

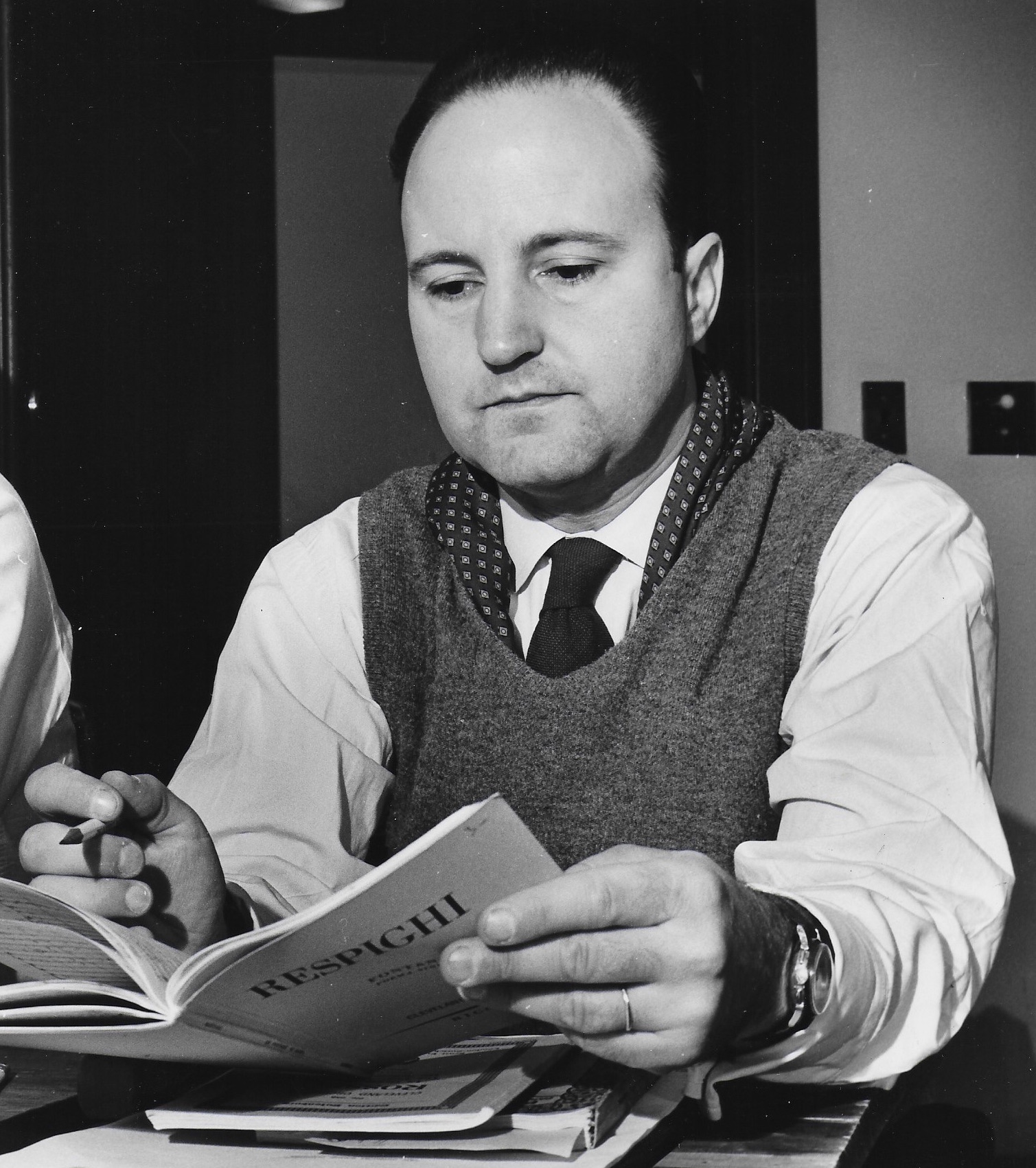

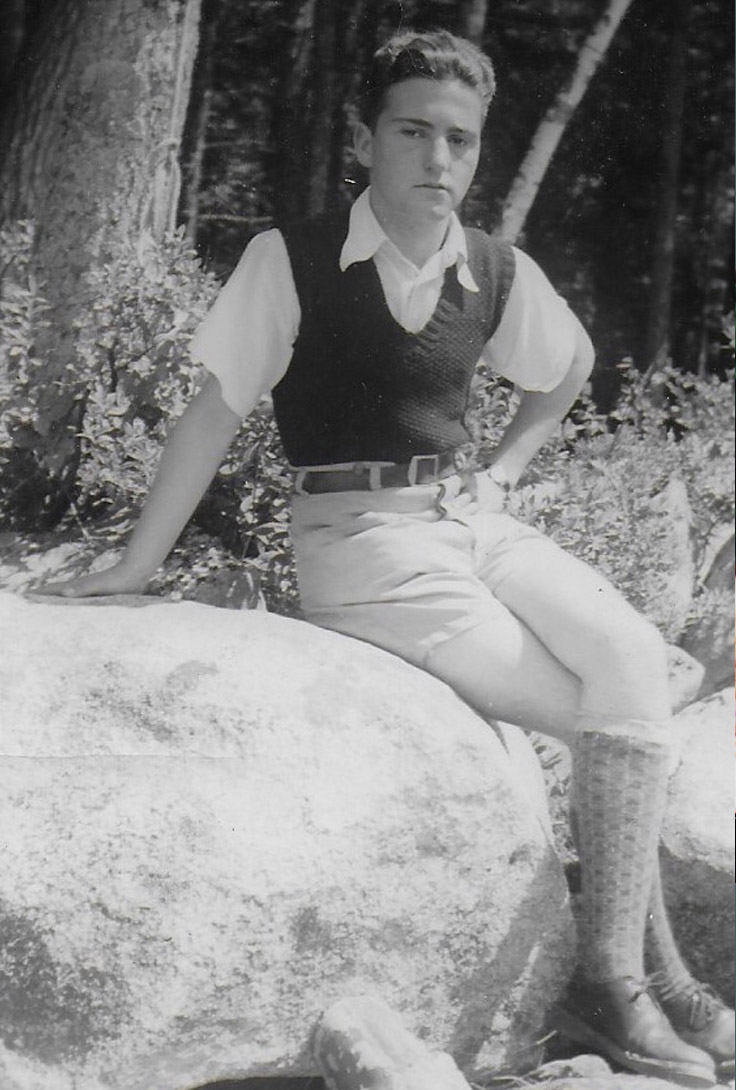

Klaus Roy 1925

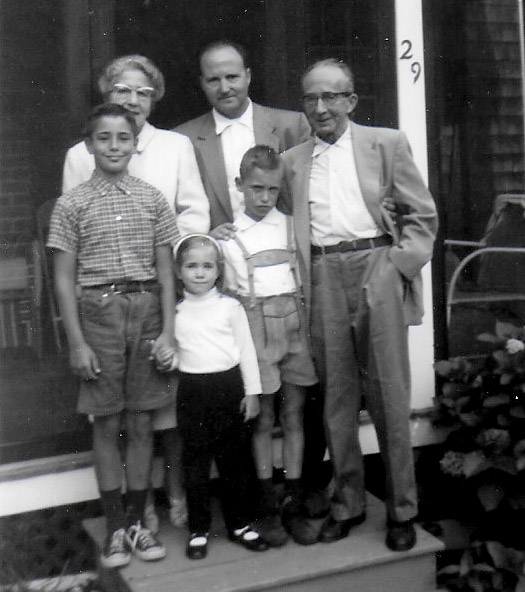

Nikko Japan, 1946

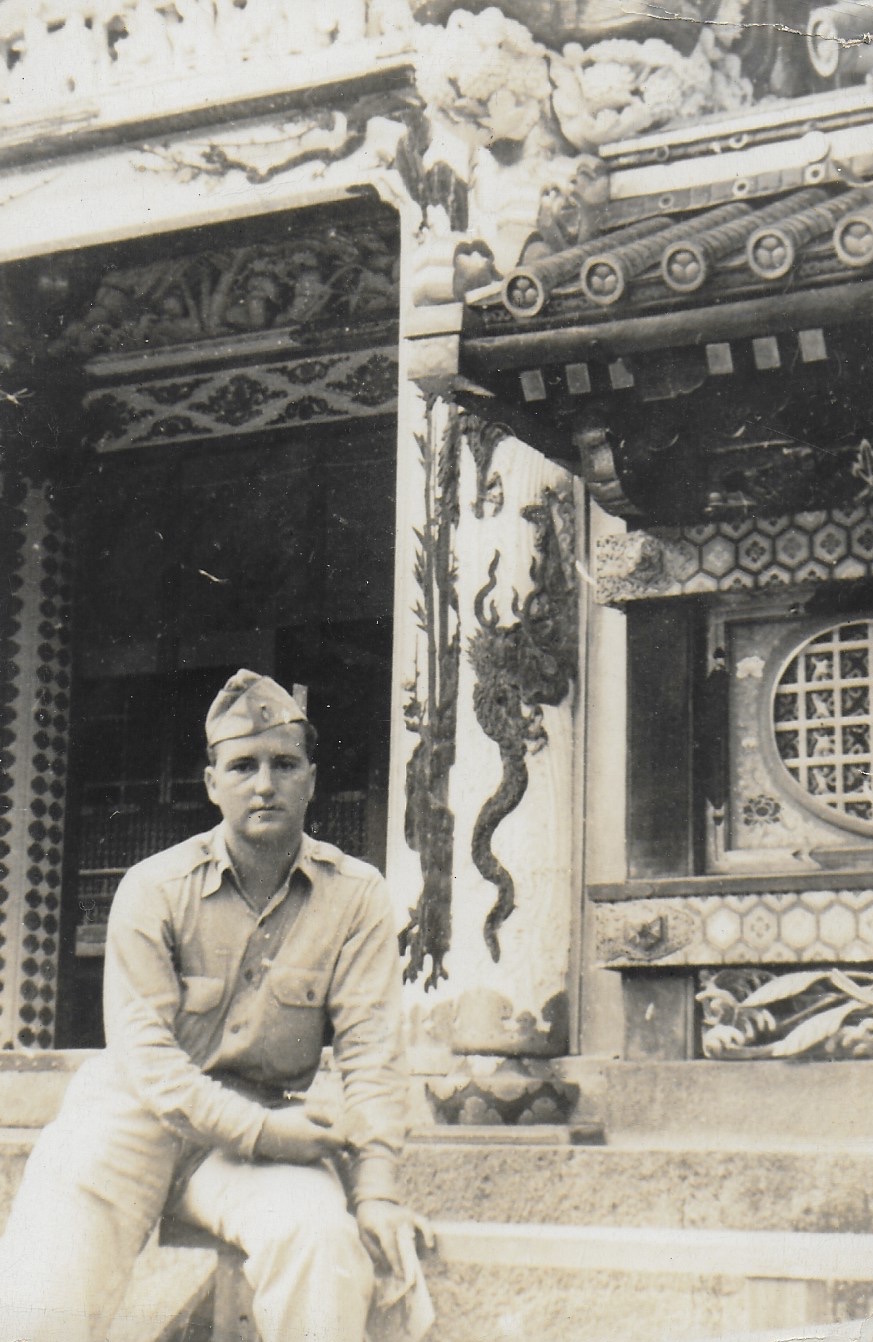

Roy was born in Vienna, Austria, on January 24, 1924. His father, Albert Roy (1893-1970), was a poet, book publisher, librarian and philatelist. His mother, Mary Koenig Roy (1902-1978), was a painter, designer, puppeteer, potter and teacher. The family fled the Nazis in 1939, moving to Sussex, England. Klaus was one of the last passengers on the famed Kindertransport, which helped spirit children out of Nazi-held countries. In 1940, after one year in England, the family emigrated to the United States. An uncle, Leo Roseneck, a noted pianist and accompanist, had emigrated earlier and taught for decades at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia.

Upon arriving in the United States, Klaus Roy enrolled in the Cambridge School in Weston, Massachusetts, and later matriculated to Boston University, first as a piano performance major and later as a musicology student. World War II intervened and Roy, by then an American citizen, served in the U.S. Army Intelligence Corps as a German interpreter. Upon receiving his commission as lieutenant of infantry, he was assigned to General Headquarters in Tokyo. In the last days of the war, he started a newspaper and began a school for servicemen, offering courses in history, language and music.

After the War, Roy returned to Boston University and studied with famed musicologist Karl Geiringer. Roy graduated in 1947 with a Bachelor of Music degree and Phi Beta Kappa honors. In 1949 he earned a Master of Arts degree in composition from Harvard University. While at Harvard he worked periodically with composer Walter Piston.

In 1948, Karl Geiringer invited Roy to teach elementary composition and to establish a music library at Boston University. During his years in Boston, Roy also worked as a music critic for the Christian Science Monitor for which he wrote more than 400 articles and reviews of concerts, books and recordings. Concurrently he developed a music criticism course and produced programs for Boston University’s radio station. He also authored articles for Stereo Review, Stagebill, and other periodicals.

Klaus Roy’s introduction to Cleveland came in 1956 when Columbia Records producer David Oppenheim asked him to write sleeve notes for three records on Columbia’s Epic label. These were Cleveland Orchestra discs. A year later, conductor George Szell asked Roy to fill the position of annotator and program editor for The Cleveland Orchestra.

Roy and his family moved to Cleveland in early 1958—beginning 30 years of employment with the Cleveland Orchestra. His twice-weekly pre-concert talks for the Cleveland Orchestra began in 1972 and continued for more than 15 seasons.

Roy’s duties at Severance Hall included producing all publications of the Orchestra and the Musical Arts Association—including program books, annual reports, press releases, fundraising literature, and books for (summer) Pops concerts. Every program from 1958 to 1988 contained Roy’s articles and annotations. He also acted as informal archivist, answering music-related queries, serving as guardian of historical artifacts and documents, creating exhibits in the Green Room, and conducting tours of Severance Hall. As an extension of his written annotations, Roy presented hundreds of concert previews: informal lectures that preceded subscription concerts. He also interviewed scores of conductors and guest artists for WCLV broadcasts of Cleveland Orchestra concerts.

Over the years, Roy also annotated more than 200 albums for Columbia and its Epic label, as well as the Haydn Society, Urania, and the Time-Life record series.

In 1960, Roy helped found the Cleveland Arts Prize, which now reigns as the longest-standing award of its kind in the United States. The Arts Prize honors Northeast Ohio artists of all kinds: literature, theater, visual arts, dance, architecture and music. In 1965, Roy received the year’s award for excellence in composition.

In 1975, while still employed at Severance Hall, Roy joined the faculty of the Cleveland Institute of Art, where he taught a course in music for art majors. In 1986 he became adjunct professor at the Cleveland Institute of Music. The following year, CIM awarded him an honorary Doctor of Music degree.

From 1981 to 1983 he was featured in the Signature Series produced by WVIZ, Cleveland’s public television station. These essay-type programs covered a variety of subjects, including Roy’s thoughts on science, astronomy, and social and political issues. It was these critiques and countless commentaries to newspapers that earned him the title of “cultural activist.” Many artistic institutions—the Cleveland Area Arts Council, the Cleveland Chamber Music Society, the Cleveland Composers’ Guild, the University Circle Recital Association and others—involved him as consultant and/or trustee.

Klaus Roy’s compositional life was equally illustrious: more than 400 pieces and some 130 opus numbers. Dozens of his works have been formally published. Rather than avant-garde, his music is frequently characterized as lyrical and melodic. Roy also wrote two widely-performed chamber operas. In 1957, opera producer and conductor Sarah Caldwell presented Roy’s first opera, Sterlingman, Op. 30, for Boston’s WGBH-TV. In 1983 the Cleveland Zoological Society commissioned the second opera, entitled Zoopera: The Enchanted Garden. That same year, members of The Cleveland Orchestra premiered this opera in the Zoo’s amphitheater.

Most of Roy’s music is short. His two operas are 45 and 30 minutes in length. According to Roy, his heavy work schedule mandated brevity in his compositions. Many artists and conductors have performed his works, not only in Cleveland, but throughout the country and around the world. This performance activity continued after Roy’s retirement in 1988. During the 1991/1992 music season alone, various musical groups performed more than 30 of his works, including ten first performances.

Among Klaus Roy’s many strongly held convictions was his firm belief in the viability of contemporary musical works. Although he felt a loyalty to the past and respected and revered the old masters, he championed new art. He pleaded for tolerance and acceptance of contemporary compositions, and said these would require the same kind of study and understanding of preceding artists: If music is to flourish, it must change. Roy recognized the natural resistance to change which exists not only in the arts but in other areas of endeavor. He encouraged the public to go beyond that which is comfortable and conventional and to learn to appreciate what is new and innovative.

After his retirement in 1988, Roy spent more time with intellectual and recreational interests. He continued to teach, lecture, write and publish. He also assisted with the publication of “Not Responsible for Lost Articles,” a compendium of his essays published previously in The Cleveland Orchestra program books. His second wife, Gene Burdick Roy, whom he married in 1970, shared his many interests. Mrs. Roy was a long-time teaching-faculty member at the Cleveland Institute of Music. Together they conducted eight summer music festival tours under the auspices of WCLV-FM.

Throughout his career, and almost to his death in 2010 at the age of 86, Klaus Roy distinguished himself as an annotator and editor, composer, critic, scholar, journalist, television and radio commentator, educator, tour host, concert narrator and lecturer.

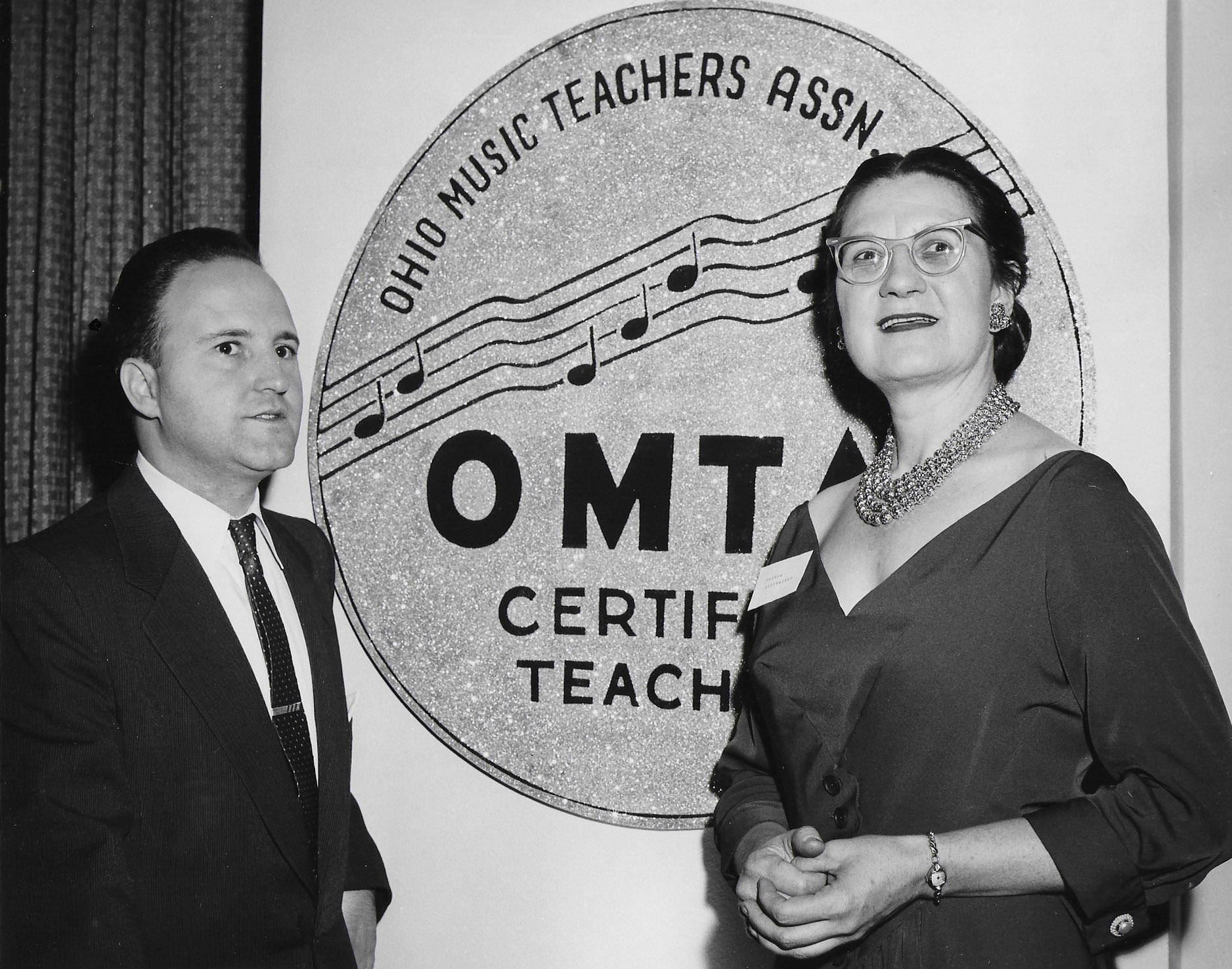

With Frieda Schumacher, 1958

With Cloyd Duff, early 1960s

With Roberta Geismer, Eunice Podis and Louis Lane, 1964

With Louis Lane, early 1960s

Scene from “The Enchanted Garden,” 1983

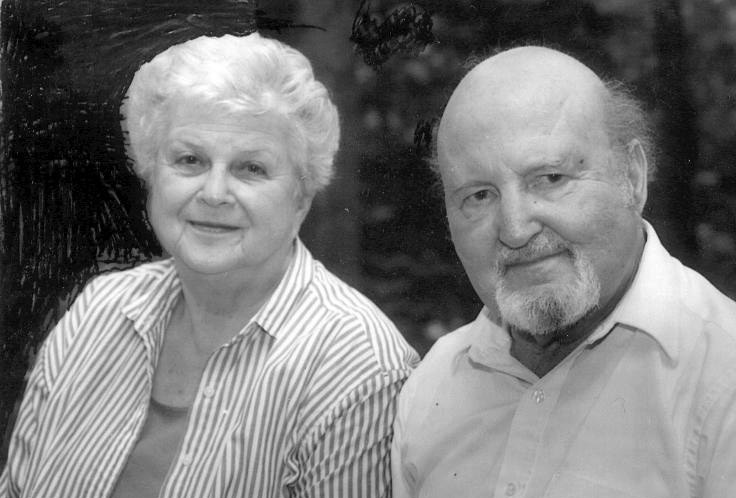

Klaus and Gene Roy, 2001

With Eunice Podis, 1964

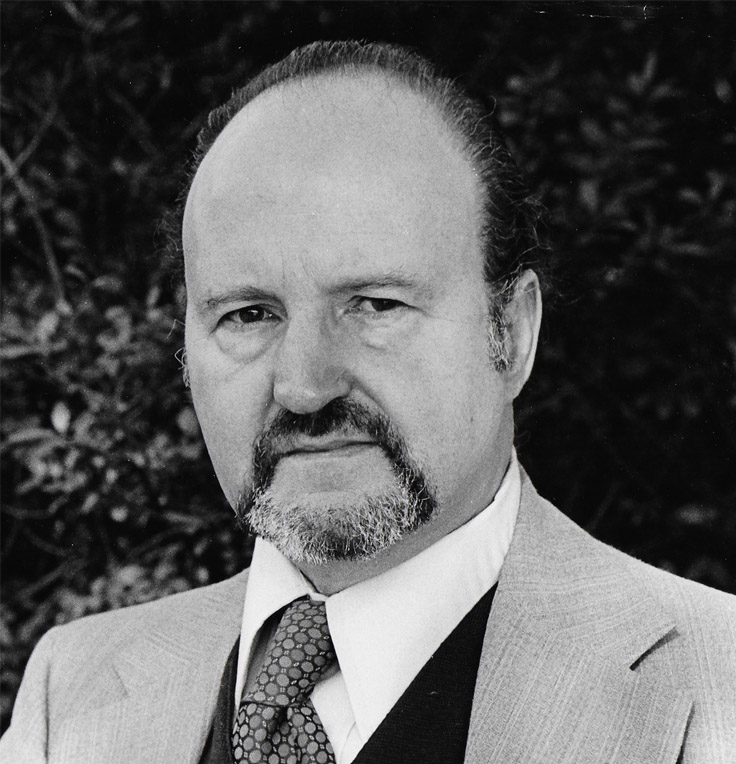

Klaus Roy 1977

With Walter Piston, 1960

With Glenn Gould, 1962

KGR, 1940